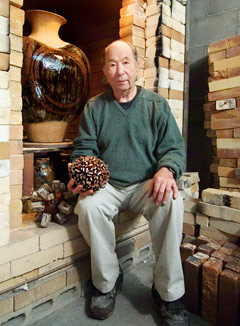

Colby-Sawyer College Hosts Retrospective Exhibition of Works by Potter Gerry Williams, New Hampshire's First Artist Laureate and a Living Treasure

The Colby-Sawyer College Fine and Performing Arts Department will present “Gerry Williams Retrospective: A Life in Clay,” an exhibition of more than 100 works spanning the 60-year career of this internationally recognized master craftsman, teacher, author and lecturer. The exhibition highlights original techniques that Williams brought to the ceramic arts and explores the diverse influences that shaped his philosophy of life and approach to his craft.

A longtime resident of Dunbarton, N.H., Williams is the founder of The Studio Potter journal and co-founder of the Phoenix Workshops, and he has been a model and source of inspiration for ceramic artists around the world. Williams was selected as New Hampshire's first Artist Laureate by Governor Jeanne Shaheen in 1998, and in 2005, he was honored with the state's Lotte Jacobi Living Treasure Award.

Co-curated by Jon Keenan, professor and chair of Fine and Performing Arts, and Gerry Williams' daughter, Shelley Williams Westenberg, the exhibition opened on Thursday, Sept. 15, at the Marian Graves Mugar Art Gallery, Sawyer Fine Arts Center, and will continue through Saturday, Oct. 22. The gallery will be open Monday-Friday, 9 a.m.–5 p.m.

Williams once wrote, “Potter is what I do, who I am, where I come from.” He was born in Asanol, Bengal, in India in 1926, the son of American educational missionaries who ran a school there. His father worked with and was befriended by Mahatma Gandhi, and the young Gerry Williams embraced the Indian leader's philosophy of non-violence and reverence for handicraft and local agricultural economies in which people lived in mud houses, grew food and made products that others used in their daily lives. Williams internalized Gandhi's teachings and knew he would one day seek a vocation that allowed him to pursue an ethical and politically responsible life.

“It was the symbolism of Gandhi's life I accepted and which became part of my ethics and moral life,” Williams explains. “It was his interest in hand work and social activity and the importance of living within your means. He allowed me to say 'what am I going to do with my life that will be ethical and politically responsible?' Being a potter is what I came to believe the answer to that question was.” Many years later, Williams sees the “spirit of India” in his work. “The ambiance, the dignity of crafts, the importance of manual labor, the spiritual necessity of the humanistic core of crafts, all come from my background in India.”

Williams came to the United States in 1943 to attend Cornell College in Iowa, and after a year he was drafted into military service in World War II. His opposition to the violence of war led him to declare himself a conscientious objector; he left college, spent time in prison and served alternative service through clearing trails and volunteering as a subject for malaria testing. “It was important to me to object to killing people. We had to prove they were the oddballs, not us—the 'odd' intellectual people,” he says.

In 1950, Williams was drawn to New Hampshire's thriving community of studio potters and studied with Vivika Heino and Richard Moll at the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen. He was also deeply influenced by master potters Edwin and Mary Schier and Jim and Nan McKinnell, as well as by the 18th-century potter Daniel Clark, whose diary he studied to learn about techniques for creating utilitarian earthenware.

Within a few years, Williams established a studio in Concord, and like Clark, created functional earthenware made with local red clay. He met and married Julie Blake, a local radio host, and in the late 1950s, they built a home and studio in rural Dunbarton. They raised their children, Shelley and Jenny, whom Williams lovingly calls “two of the most significant children in the entire world.”

By the early 1960s, Williams was well known and respected as one of the few potters in the country able to make a living as an independent craftsman. He became a technical master and studio potter-artist, developing new wet-fire techniques and a photo-resist process in which images are laid directly onto vessels and fired. His interest in color led him to master the elusive Copper Red Glaze, evoking his own brand of brilliant, rich red hues, and he experimented with vibrant cobalt blues and copper greens, as well as with muted browns and blacks created by glazes infused with iron and other oxides.

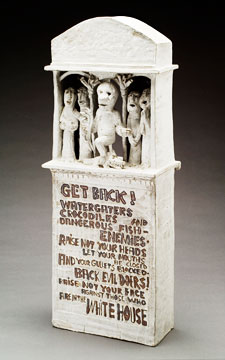

While Williams' focus on functional earthenware pottery persisted, he pushed his firing techniques for clay to its upper temperature limits and gradually incorporated high-temperature stoneware and porcelain—wheel-thrown and slab-built, gas-fired and wood-fired—which became his principal mediums. His work evolved in response to the people and techniques he came into contact with and to contemporary social concerns and world events. While he continued to produce well-thrown functional pots for daily use—bowls, cups, jars and teapots—he moved toward sculptural and pictorial constructions that allowed him to tell stories and express social, political and satirical commentary with words and effigy figures.

In an address to the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen in 2006, Williams explained his evolution as a potter. “When the time came for me to choose a profession, I believe I was led into ceramics as an alternative route influenced by my background of social interests and principles, identifying themes relating to politics, race, war, assassinations, social justice and pain, all emerging from my background and life,” he said. “Primarily I am a potter making functional objects, but as I observe social and political behavior around me in this country, I cannot help but put my feelings into articulated clay and say what I feel. These, too, have come from my background in India and with Gandhi. I have made sculpture dealing with Martin Luther King's assassination, with President Kennedy's death, with racial prejudice, with the Watergate scandal, and other such themes.”

In 1971, Williams' studio burned to the ground, and within two weeks the community of potters in the state had converged on his Dunbarton property and rebuilt the entire studio. “As much as potting is a solitary activity, the rebuilding of the studio was a wonderful communion of spirits,” recalls Shelley Williams Westenberg. “That was what we were all about, a communal way of living. It was a testament to Dad's influence and ability to transform people's thinking.”

Other than his pottery and sculpture, the most important endeavor of Williams' career was his founding in 1972 of Studio Potter, the international journal that became one of the most influential and literate art publications. Gerry and Julie Williams traveled the world to interview potters and celebrated their regional practices, history, techniques and lives in the publication. In collaboration with Julie, Gerry wrote for and edited Studio Potter and administered its non-profit foundation for 30 years, connecting the worldwide community of studio potters.

The re-building of his studio inspired Williams and fellow potter Armand Szainer to create a summer school in Dunbarton called the Phoenix Workshops, which attracted potters from around the world as teachers and students. “We had a core group of students, and potters were invited to come from Austria, England and Germany. They would sleep in tents with wall-to-wall carpeting, and Mother would entertain and feed them,” says Westenberg.

John Hartom, a North Carolina-based potter and co-founder of the Empty Bowls Project, attended the Phoenix Workshops for several years and met his wife and project co-founder, Lisa Blackburn, there. “For me, it was an opportunity to learn about being part of a community…It was a safe place where I was cared for and never judged. I learned about creating a lifestyle that embraced everyone…(and) about ritual, ceremony, celebration, responsibility, service, gardening, cutting firewood, packing Studio Potter magazines and participatory democracy. Yes, I learned to make better pots, but that was certainly not the most important thing. Through the remarkable behavior of Gerry and Julie, I learned to be a better person.”

Throughout his career, Williams has contributed to his field by creating and exhibiting his work and sharing his knowledge and experience of studio pottery. He has participated in and initiated conferences and received numerous awards and honorary degrees. And as he hoped, he has made a living and a life independently, responsibly and ethically, cared for his family and helped to build and sustain a community of studio potters.

Since his wife Julie's death, Williams is subdued and less active. “She was my reason for living,” he says quietly. At age 85, he still lives in the Dunbarton home they built, surrounded by paintings, photographs and, of course, pottery and sculpture, and is often visited by children, grandchildren and friends. He looks forward to the next exhibition of his work and the prospect of like-minded spirits gathering in celebration of the craft of studio pottery. Potter is what he does, who he is, where he comes from.

“I tried to share what I had and engage the people around me,” he says in his simple and understated way. “It's been a wonderful life.”

-Kimberly Swick Slover, director of communications, Colby-Sawyer College

This piece is based on an interview with Gerry Williams and Shelley Williams Westenberg in June 2011, with writing and research assistance from Michael Boylen, retired professor of ceramics at Marlboro College, and the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen.