Growing a Culture of Research

by Kimberly Swick Slover

Last summer, juniors Paul Boynton and Jenisha Shrestha spent most of their days dressed in waders and boots, tromping through the streams that flow gently into New Hampshire's Lake Sunapee. Their long days of field research— collecting water, aquatic invertebrates and fish— made for the most extraordinary learning experiences of their lives.

Their research internships were part of a project led by Associate Professor of Natural Sciences Nicholas “Nick” Baer, focused on the roles ecological, chemical and landscape factors play in determining how mercury accumulates in invertebrates and fish—and the extent to which this toxic metal moves through them and into the region's food webs. Westerly winds carry mercury, a byproduct of coal-burning plants in the Midwest, to the Northeast, Professor Baer explains, where it can contaminate watersheds and pose serious health risks to wildlife and people.

Following training last spring with Professor Baer and his first two research assistants, 2012 graduates Jessica Chittering and Adam Wilson, Boynton and Shrestha worked with a team of students from other colleges to build 50 traps made of plastic piping and fine mesh. Boynton and Shrestha deployed the traps in 10 tributaries and began the arduous work of collecting aquatic invertebrates, insects born in water as larvae that emerge into the air and on land as adults. They often spent 16-hour days collecting some 77,000 insects over the summer.

The process became easier as other researchers joined the project, which intersects with several others that involve faculty and student researchers from Bates, Dartmouth, Lewis and Clark Colleges, SUNYNew Paltz, and the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. The research teams shared samples and data, a collaboration which has created a dynamic environment for teaching and learning.

“Nick wants us to do our work in a meticulous way because our samples will be used for a lot of studies,” says Shrestha. “We have to be careful not to make mistakes.” Shrestha and Boynton's internships focused on the potential transport of mercury from aquatic to terrestrial ecosystems. “We collected invertebrates emerging from the streams and fish from Lake Sunapee. This fall we're identifying, counting, freezing and storing our samples until metal analyses can be conducted.”

An Environmental Studies major, Shrestha learned to identify most invertebrates by their scientific and common names and created a visual key with their images and characteristics, which she shares with other student researchers. She and Boynton also learned to test the chemistry of water, and to fish and conduct lab analyses of their samples, yet some of their most rewarding experiences came through daily interactions with people on their research team.

“We were a diverse group —biology, chemistry, environmental studies and science majors—working together for four months,” Shrestha says. “It was interesting to share what we knew, teach others and learn in the same process. One of the good things was all the connections I made with the Lake Sunapee Protective Association and the scientists from Dartmouth and other colleges. The experience inspired me.”

A native of Nepal, Shrestha hopes to return one day to work in her country. She communicates with her family via Skype every few weeks and they are beginning to accept her career direction. “Medicine, engineering and business careers are the most popular in Nepal,” she says, “but they are starting to understand what I do here.”

Shrestha has worked closely with Ramsa Chavez- Ulloa, a Ph.D. candidate at Dartmouth College, in a laboratory on identifying and storing invertebrates. “I get a lot of inspiration from Ramsa, who is doing a study here and a similar one in her native Costa Rica. I think about doing something similar in Nepal, which is rich in water resources.”

Boynton grew up in a military family that moved often, and for college, he gravitated to New Hampshire. “I've always liked being outside and in nature, and I really like to learn. Last summer I couldn't believe I was getting paid to walk though New Hampshire streams and do all this awesome stuff. During my internship I thought, 'This is what I love to do, so I must be in the right place.'”

His internship has given him an appreciation for how much work goes into each data point on a graph. “I've learned a lot in my classes, but there's no substitute for handson work in the field. It was interesting to have so many perspectives on everything we were doing— from people my age, Ph.D. students and professors,” Boynton says. “I learned a lot about group dynamics. I was pretty good at it, which is important in science because you need to get along and work with other people.”

The project kept evolving— from water chemistry and insects, to fish and community service, to intense laboratory work— and it all intrigued him. Boynton learned the importance of being patient, organized and meticulous. The experience of working around smart, highly motivated people who love what they do inspired Boynton and lifted his expectations of himself.

“You learn a lot from their experiences and gain some of their wisdom,” he said. “I talked to Nick so much, and not just about the research. You're not just a number and people give you personal advice. It was cool to have a project that wasn't related to a grade and wasn't limited by a class period—and that might connect to what I do later on in my career.”

Professor Baer says that working with students and colleagues on this research has been one of the highlights of his academic career.

“Our collaborative research project benefits the students and the overall research effort. The students are an integral part of most aspects of our research. Many hands make the enormous task of collecting, processing, data management, analyses and dissemination possible for us,” he explains. “Our student research assistants have become part of our research community and are mentored not only by me, but also by the project's co-principal investigator at Dartmouth College, Celia Chen, her research technician, Hannah Roebuck, a Ph.D. student Ramsa Ulloa- Chaves, and many other collaborators. Clearly our students' skills, dedication, attention to detail and strong work ethics will serve them well in their future career paths or graduate school.”

Chen, a ecotoxicology researcher and Professor Baer's project mentor, has been inspired by how her colleague incorporates students like Boynton and Shrestha into so many aspects of his teaching and research. She describes Baer as an “enthusiastic, can-do kind of scientist who is an absolute pleasure to work with.”

“Nick has a spontaneous but organized style of working with his students and collaborators. The Colby-Sawyer students… are all very dedicated and extremely hard working,” Professor Chen says. “They have been very responsible and committed.”

A New Vision for Liberal Arts Colleges

Professor Baer's research, and his ability to involve students, is part of the rapid and radical change at Colby-Sawyer College that began in fall 2010, when the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awarded a five-year, $15 million grant to ten colleges in the state to create a biomedical research network. Known as the New Hampshire Idea Network of Biological Research Excellence (NH-INBRE), the program is led by the state's two research institutions, Dartmouth College and the University of New Hampshire, in collaboration with eight undergraduate institutions, including Colby-Sawyer College.

With an infusion of $1.25 million over five years, Colby-Sawyer launched two pilot research projects led by Natural Sciences Professors Baer and William Thomas, along with several smaller faculty-driven projects. Dozens of students in the college's science programs—from biology, environmental studies and exercise and sport sciences, to health studies, nursing and psychology— have been trained as researchers within their professors' projects and in NH-INBRE-sponsored summer research programs. In just over two years, a research culture has begun to grow among Colby-Sawyer's faculty and students that connects them to other researchers in New Hampshire and beyond.

For Professor of Natural Sciences Benjamin Steele, who oversees the project at Colby-Sawyer, the most exciting impact has been on Colby-Sawyer students. “NH-INBRE has enabled us to develop a research culture that allows students to do a piece of a research project that contributes to a larger body of scientific knowledge,” he says. “It's much more intense and collaborative than the individual research projects our students have done in the past.” $Like Moths to a Flame

Cells are the essence of life. They adhere to one another to create the tissue and bones of multicellular organisms, to heal wounds, and in abnormal conditions, to form and spread diseases such as cancer.

Understanding cellular adhesion is an important area of cancer research and the focus of Professor Bill Thomas's ongoing research as a cellular biologist. He became interested in this topic as a graduate student at Princeton University and has continued to pursue it every summer for the past 13 years at the Institut Curie in Paris.

For the first time since he joined the college in 1991, Professor Thomas is able to engage his students—18 in all—in his research. Since 2010, he has built a network of student researchers to explore different paths to a central question: How do cells develop the adhesion that holds them together? The answer could ultimately help to stop the spread of cancer.

In the narrow Biology Laboratory at the Curtis L. Ivey Science Center on a Friday afternoon in November 2011, space is tight as a group of curious freshmen and sophomores huddle around Faedhra “Fafa” Wagnac '12 as she performs an experiment. Wagnac, a Biology major with minors in Chemistry and Environmental Studies and one of two paid research assistants in this project, places flasks of carcinoma cells into a gyratory shear, setting it into motion at 200 rpm for 30 seconds. Her project replicates, with simpler, less expensive equipment, an experiment Professor Thomas conducts in Paris that seeks to quantify whether cell-to-cell adhesion strengthens over time.

Nearby, Maria Cimpean '13, a Biology major with a minor in Chemistry, sits by the laminator flow hoods, carefully transferring, or “passaging,” cells from one flask to another. Cells go through division cycles, and Cimpean's goal is to determine whether cells are more adhesive at certain stages of their cycles.

Like Wagnac, Cimpean works slowly while explaining each step to two underclassmen standing beside her. Completing the experiment, she begins to clean the equipment she has just used. “You have to disinfect all the equipment carefully every time you use it,” she tells her trainees, sounding a bit stern, “to avoid contamination.”

Cimpean learned this lesson the previous summer, when she arrived in the lab after a weekend to find a white film growing in the bottom of several cell culture flasks in the incubator. She knew there was a problem, and began to search for answers online. She believed it was a fungal contamination and documented her findings before contacting Professor Thomas in Paris. He confirmed her suspicions and helped her outline an action plan. It took an entire week to sterilize the incubator and equipment. “Sometimes you learn the most from your mistakes,” Cimpean says.

Part of Cimpean's and Wagnac's roles includes recruiting and training more students for the project. “When I ask them what they want to do in the lab, they usually say, 'Something cool,'” Cimpean explains. “But research is not all glamour and fun. There are supplies to order and beakers to sterilize and solutions to prepare. And once you get data, it requires analysis and developing and editing images. Research takes a lot of patience and perseverance.”

Professor Thomas bursts into the lab to check on his student researchers before rushing back to a classroom where other students wait to talk to him. Soon he's back in the lab to chat with Cimpean about the American Society for Cell Biology conference where she will present her research the next week.

In his office, Thomas concedes that it's hard to balance teaching with oversight of student researchers. “It takes an enormous investment of energy to create a research environment. I'm drawn in multiple directions, according to students' needs,” he says. “But research has had a tremendous effect on students. They hope to go on to medical school. They're drawn like moths to flame. It's a powerful learning experience.”

His students are learning more than tissue culture techniques; they are experiencing the excitement—and the tedium—that is research. “Just today, after Fafa has done multiple tests, the data are beginning to support her hypothesis. She has a chance to do something that's never been done before, but it's day-to-day persistent work. Students need to know that this is what's required, and learn to plan ahead, learn to adapt and pay close attention to detail. They have to be poised to take advantage of opportunities.”

Women as Research Subjects

Inspired by her father's work, Kerstin Stoedefalke, professor of Exercise and Sport Sciences, teaches and researches the effects of exercise on human health. For more than 20 years she has conducted research during many summers at the University of Exeter in the U.K., where she earned her Ph.D., and she has often been frustrated by the lack of baseline research in her field that includes women as subjects.

When Professor Stoedefalke learned of the chance to involve students in her research projects, she designed a study that would engage students both as researchers and research subjects. She wanted to test whether the current guidelines for measuring energy expenditure during walking exercise—which are used as the basis for weight loss and other health programs —are accurate for women as well as for men.

While researching current guidelines, Professor Stoedefalke was surprised to find that the most recent were published by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) in 1975. Interestingly, her father, Dr. Karl Stoedefalke, was part of the research team that tested the male subjects to develop the appropriate metabolic equations for these guidelines.

With NH-INBRE funding for student researchers in place, Professor Stoedefalke's study would require extensive recruitment and testing of more than 100 women, ages 18 to 22. Early in 2011, she recruited Madison Hawkins '12, an Exercise Science major in the pre-med curriculum, as an intern and later as a research assistant. Hawkins began her internship by creating a PowerPoint presentation about the research project, and visited numerous classes with the hopes of recruiting student volunteers.

A second Exercise Science student, Justine Sachetta '13, joined the project, and she and Hawkins recruited and tested 62 participants by the end of the year. “We have students from all majors, but the ones who are most interested tend to be in body-related majors like ESS and nursing,” Sachetta explains.

“Research helps solidify the concepts I learn in the classroom,” Hawkins says. “It's a good opportunity to step up and try out what's in the textbooks. I like intercollegiate sports and I like research, so I really want to do human performance research.”

Professor Stoedefalke points out a major difference between her study and the two pilot research projects. “We're involving the community and using human subjects rather than petri dishes. Sometimes our research subjects don't show up.

We can't just keep them in the fridge,” she says, with a laugh. “But it's a good training ground for our students.”

On a late fall afternoon in 2011, Hawkins and Sachetta are scurrying around the Human Performance Laboratory in Mercer Hall, preparing a research subject for a test. They fit the student with a metabolic analyzer mask that connects to a computer program which measures— via a gas exchange analyzer—the volume of oxygen (VO2) she utilizes while walking on a treadmill. Knowing that 1 liter of oxygen utilized by the body is equivalent to 5 calories expended, the test will determine the energy cost of walking at various speeds and grades.

Hawkins instructs the student to walk at a constant speed of 3.2 mph during a three-minute warm up and in three stages of 2-, 4- and 6-percent grades. She and Sachetta record the student's VO2 rate when she reaches a steady state in each stage, the point at which her heart rate remains steady for 30 seconds, before moving her to the next stage. Later they will compare her metabolic data and that of dozens of other female students who have participated, to the equations in the ACSM guidelines.

“We're finding there is a difference,” Hawkins says of their early results. “Our data suggest that the (ASCM) equations at the 4-percent and 6-percent grades overestimate the calories that are actually utilized at that stage.”

More than a year later, Sachetta and Katherine Coughlin '13 continue to work on the project and are still yielding different results with female subjects. Professor Stoedefalke says the study suggests that one should not assume that research conducted on male subjects will produce the same results for women.

“Our next step is to publish the research results,” Stoedefalke says. Meanwhile, she is working on a new research project, as a co-investigator at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, focused on the effects of regular exercise in breast cancer survivors. Professor Stoedefalke anticipates that Colby-Sawyer students will play an integral role in the data collection.

Student Scientists

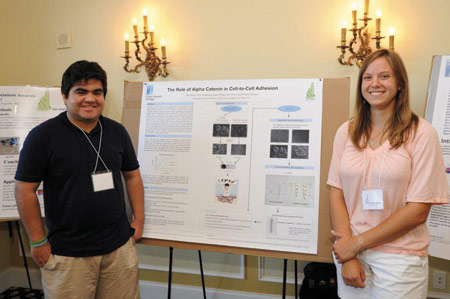

An exuberant din fills President's Hall at the Mountain View Grand Resort in July 2012, as more than 100 students from New Hampshire colleges present their biomedical research. With the spectacular backdrop of the Presidential Mountain Range, the Colby-Sawyer students are clustered around their poster boards—on which their research has been crunched into bytes of copy and colorful images—and respond to questions posed by passersby.

Nursing major Katuiscia “Kasey” Correia '13, who attended the meeting during a 10-week Summer Research Fellowship in Nursing (iSURF-N) at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, says research has become a big part of her profession. “There's a big push for evidence-based practice, so it's good that we're adding research to what we do. We're getting exposed to all types of nursing, clinical nursing, nurse practitioners and nurses doing clinical trials to improve nursing performance and patient safety,” she says. “You can be at the bedside or have an administrative role or go into clinical research focused on improving the quality of care.”

As she and her fellow student nurses shadow nursing specialists in the course of a day, Correia experiences the interdisciplinary nature of the medical field. “You work directly with the patients, but you also network with doctors and medical students and administrators and specialists. It's an amazing experience.”

Nearby, Professor Stoedefalke's research assistants, Justine Sachetta and Kathryn Coughlin, answer questions about their work and futures. Sachetta plans to go to graduate school for exercise physiology and hopes to work in obesity and cardiac programs for a clinical hospital. Coughlin has enjoyed working with other students in the lab and hopes to combine research with clinical practice.

Through another research project, Coughlin discovered the rewards of working with elderly people. “I'm thinking about doing a study to show how exercise can benefit the elderly, maybe in a master's program in recreation therapy,” she says. “When I started working with them, they told me, 'I'm old! I don't like to exercise,' but after awhile they saw that exercise helped them.”

Professor Thomas's student researchers are also out in force. Yangjinqi “Vigil” Vu '14, a Biology major with Chemistry and Environmental Science minors, is a hard-working student who has been spotted in the lab at 1 a.m. She finds her work on cell adhesion both exhilarating and challenging. “If we can figure out how adhesion works, maybe we can prevent the cancer from migrating through the body,” she explains.

Many students, like Jose Diarte '13 of Paraguay, see their research training as a means to a higher goal. “When we were freshmen, we didn't have these kinds of opportunities. It's something I really appreciate,” he says. “We have the chance to change the world. I want to do epidemiology, but this will be good background for me when I apply to grad school.”

In this moment, in the grand hall packed with buoyant student researchers and beaming faculty mentors, the introductory speech delivered the day before makes perfect sense.

“The impact of the program on undergraduate researchers has been enormous,” said Ronald K. Taylor, professor of microbiology and immunology at Dartmouth's Geisel School of Medicine and the project's principal investigator. “Now every NH-INBRE institution has a program that revolves around the new culture of experiential learning through research opportunities. This new culture has truly been transformative.”

Looking to the Future

In 2014, the NH-INBRE program will apply to the National Institutes of Health for another fiveyear grant to continue to expand its culture of research across the state. Chuck Wise, the project manager at Dartmouth, expects the state's grant will be extended.

Professors Baer and Thomas plan to apply for external sponsored research funds, and several newer faculty members have brought their research projects to the college, attracted in part to Colby-Sawyer by the potential of NH-INBRE support.

Colby-Sawyer students have gained valuable skills and experience in research methods and in presenting their findings, not only at the annual NHINBRE meeting, but also at regional and even national biomedical research conferences. Graduates' horizons have already stretched to include new possibilities, including publishing their research in scientific journals, employment in clinical laboratories, and graduate school in a variety of fields.

NH-INBRE is a “partnership of peers,” integrating research into the curriculum of small liberal arts colleges, says Wise. The program meets schools where they are on the research continuum, and for Colby-Sawyer, which was already moving along this path, the infusion of research funds has accelerated its progress.

“We're funding the most effective way to give students the research experience they need, and Ben (Steele) shows an unusual ability to get the biggest bang for the buck,” says Wise. “The research budgets at some schools only impact a half-dozen students, but Colby-Sawyer has involved many more faculty and students.”

One of the major cultural changes that NH-INBRE seeks to support is to bring scholarship into the realm of the classroom, which would benefit faculty, students and the educational experience at liberal arts colleges. “Typically smaller colleges see scholarship as different from teaching,” Wise explains. “We're trying to say that they are one and the same.”

As Wise says, NH-INBRE provides the forum for small teaching colleges to consider their new possibilities. While the NIH research grants will likely continue to help Colby- Sawyer build its culture of research in the short term, the college will ultimately need to sustain the momentum through independent sponsored research grants and other means.

“This is Colby-Sawyer's time to see if the research shoe fits,” says Wise.

Merging Medical Research and Practice

As a high school student in Romania, Maria Cimpean had a rare opportunity to volunteer in a hospital emergency room, where she helped the medical staff with patients who were inebriated and injured, in cardiac arrest, or suffering from multiple fractures after an accident.

“I liked the team effort during these cases and the excitement when the unexpected happened,” she said. “I discovered I'm very calm in an emergency.”

Cimpean came to the U.S. in 2009 as a Biology major, and a year later she jumped at the chance to join a NH-INBRE biomedical research project. She broadened and deepened her knowledge and skills over the next two years, culminating in her senior Capstone research project.

Last summer, Cimpean completed a 10-week internship at Boston Biomedical Research Institute in its Undergraduate Research Opportunity Core (UROC). Supervised by Dr. James Windelborn, she worked on a project focused on the developmental aspects of differentiation in embryonic stem cells.

With her research experience from Colby- Sawyer, Cimpean felt prepared to contribute to the project. “My experience with cell culture proved useful, as I had to maintain and manipulate the stem cells I was working with. I also learned a technique called polymerase chain reaction.”

Through presenting her undergraduate research at NH-INBRE and at national conferences, Cimpean has developed strong skills in science communication that helped prepare her for the final UROC presentation. “Presenting on a topic and project that was just nine weeks old proved challenging, but the support and feedback I received from the institute, its scientists, and Dr. Windelborn was wonderful,” she says.

“NH-INBRE has given me the opportunity to get involved in a research project early on in my college years. To me, it meant the first step to establishing a research culture at Colby-Sawyer,” she says. “Through NH-INBRE, students can get involved in biomedical research at a small liberal arts school. You get the liberal arts experience, the personal attention due to the small class sizes, and get to work on a research project right here on campus. To me, that is just exceptional.”

Following graduation in May, she plans to work as a research technician for a couple years, during which she will seek admission to a program that combines medical school with doctoral studies. The dual degrees will allow her to practice medicine and pursue her research interests.

“I've known for a long time that medicine is where I belong. It's what I see myself doing for the rest of my life,” Cimpean says. “What has changed after NH-INBRE and my internship is that I am strongly considering an M.D.-Ph.D. program because I would like research to be part of my future too.”